Alaska - Denali NP

Talkeetna, Alaska

Approaching the Kahiltna Base Camp

At the Kahiltne BC landing strip

Mt, Hunter inthe background

Mt Hunter 14,573 ft

Mt. Hunter 14,573 ft

Denali 20,320 ft Cassin Ridge

Denali 20,320 ft

Mt. Hunter 14,573 ft

Mt, Hunter north pillar

Mt. Foraker 17,400 ft

Mt. Hunter 14,573 ft

North Face of Mt. Foraker 17,400 ft

from R to L: Mt. Foraker 17,400 ft and Denali 20,320 ft

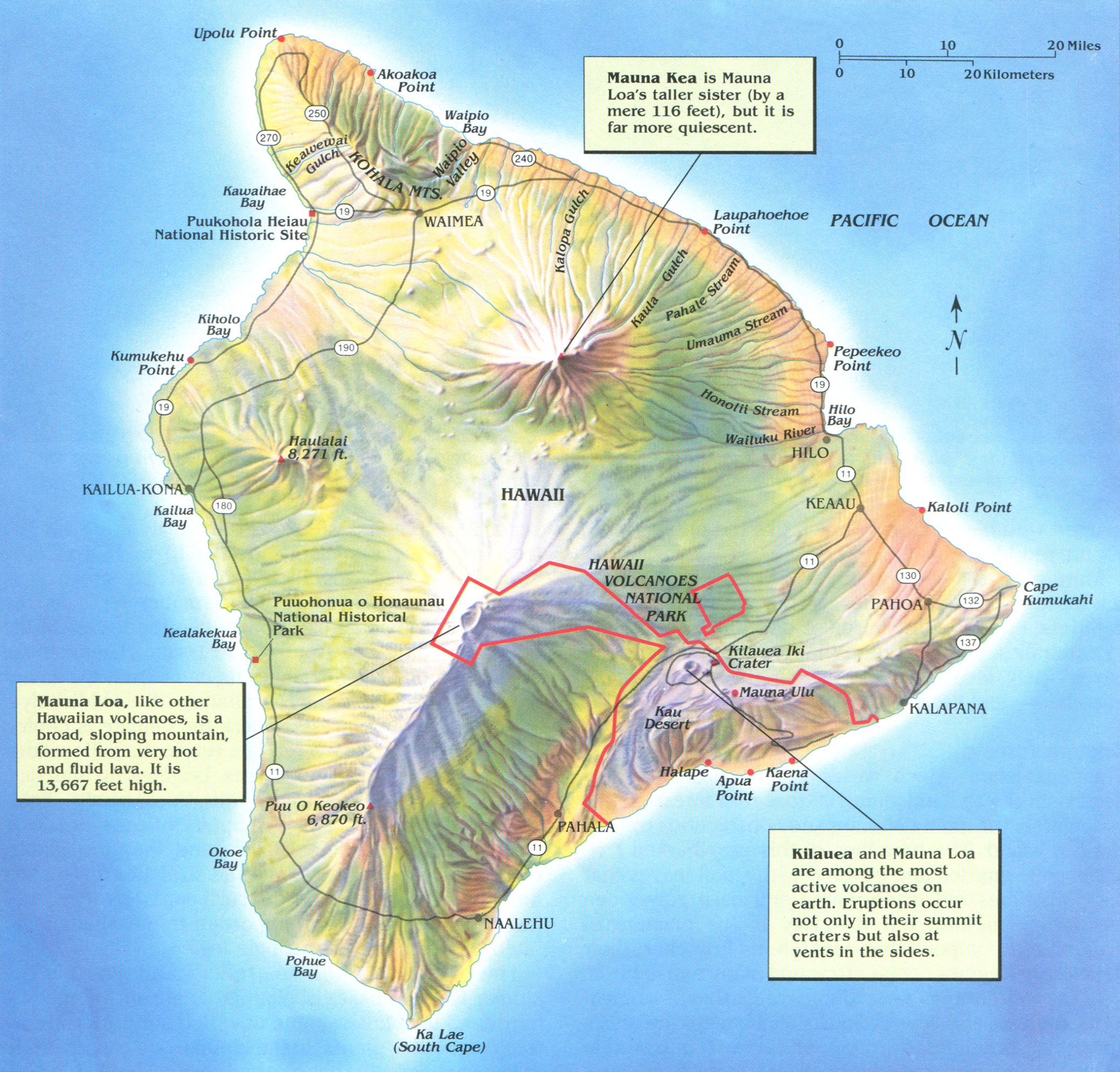

USA Hawaii

Grand Canyon NP, Arches NP, Monument Valley, Petrified Forest NP - USA

The Big Bend

Lake Powell near Page, Arizona

The Grand Canyon North Rim

The Grand Canyon North Rim

The Grand Canyon North Rim

The Grand Canyon North Rim

The Grand Canyon North Rim

The Grand Canyon North Rim

The Grand Canyon North Rim

The Grand Canyon North Rim

The Great Canyon North Rim

The Great Canyon North Rim

The Monument Valley in the Navajo Tribal Lands

The Monument Valley in the Navajo Tribal Lands

The Monument Valley in the Navajo Tribal Lands

The Monument Valley in the Navajo Tribal Lands

The Monument Valley in the Navajo Tribal Lands

The Totem pole in The Monument Valley in the Navajo Tribal Lands

The Monument Valley in the Navajo Tribal Lands

The Monument Valley in the Navajo Tribal Lands

The Monument Valley in the Navajo Tribal Lands

The Monument Valley in the Navajo Tribal Lands

The Monument Valley in the Navajo Tribal Lands

Arches National Park

Arches National Park

Arches National Park

Arches National Park

Dead Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah

Dead Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah

Dead Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah

Dead Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah

The Fingers from the road to the Dead Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah

Dead Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah

Dead Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah

Dead Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah. The view over Canyon lands National Park.

Dead Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah

Dead Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah

Dead Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah

Dead Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah

Dead Horse Canyon near Moab, Utah

Arches National Park

The Grand Canyon North Rim

Hopi Katchina Doll artist

Canyon de Chelly National Monument in Arizona

Canyon de Chelly National Monument in Arizona

Canyon de Chelly National Monument in Arizona

Canyon de Chelly National Monument in Arizona

Petrified Forrest National Park in Arizona

Petrified Forrest National Park in Arizona

Petrified Forrest National Park in Arizona

Petrified tree in the Petrified Forrest National Park

Cross section of a petrified tree

A fossil of a Jurassic ocean reptile in the visitor center of the Petrified Forest National Park

USA North Pacific Coast

Argentina - Iguazu Falls

Antarctica

Manaslu Circuit, Annapurna Circuit, Mesocanto La Trip Summary

October 22, 2011

This trip was different. It was different because I was going alone for the first time. I would be on the trail for three weeks without my usual travel companions and I have never done it before. I was curious how it would work out and whether I would like it or not. After returning from the Rowaling trip last year, David and Tony lost their appetite for more Himalayan adventures. I did not, in fact I wanted much more of the same.

I chose the Manaslu and Annapurna regions as they are relatively easy to travel in and developed. I thought that it would be a perfect trek to try on my own. I would not have to use any technical equipment and could rely on local teahouses for lodging and food. Many trekkers do not even hire local guides for the Annapurna section and they do it on the cheap. A local guide is required for the Manaslu and Naar/Phu though. I thought that Manaslu and Annapurna trekking would be more about people and cultures and less about the high Himalaya. Traveling alone would enhance this experience. The Rowaling Valley that we traveled in during the previous year, is remote and devoid of any sizable human settlements. Manaslu and Annapurna regions are quite the opposite. The Annapurna region especially, is the first region of Nepal in which trekking developed into an industry it is today.

What is the difference between trekking alone or with a Nepali guide and porter? Hiring a Nepalese guide and porters gives back to the local economy and brings one closer to the local people. Kumar, my guide, can converse with the locals, ask questions and purchase food from their gardens. We also get invited to their kitchens, homes and are offered lodging or camping near their homes. It makes the trekking experience more complete and less isolating from the Nepali culture. Through the conversations with the locals, I can learn about their life, how they think and perceive the world, what they believe in and dream about. I believe that there is more to trekking in Nepal than high mountains. Interacting with local cultures and people on human level is an integral part of the experience for me.

On the other hand, when one travels alone, the interaction with the locals is limited to the commercial exchanges in teahouses or lodges. There is little opportunity for deeper interactions mainly due to the language barrier. The trekkers usually end up hanging out with other trekkers they meet along the trail.

In Doha, Qatar I had my birthday and celebrated it by pigging out on shawarmas at some non descript strip mall. I arrived in Kathmandu from Doha on a cramped flight that went by quite fast. The airport in Kathmandu was the same place where nothing had changed in the past 17 years. It is really falling apart and it is now quite noticeable. The arriving hall had plenty of broken doors and was in an overall state of neglect. It all works though and they process hundreds of thousands of tourists quite efficiently. It felt like a dejavu since I was here just one year before.

Kumar met me at the airport with a customary garland of marigolds. The drive from the airport to Thamel (the tourist district of Kathmandu) seemed like I was just there. Kathmandu was rather tiring by now and it all seemed almost too familiar. I started to notice the dirt, the traffic and the pollution much more than last year. The stores were selling the same souvenirs and fake outdoor gear that I saw the year before and frankly, every time I came to Nepal. It seemed instantly tiring to be in this city built for 500,000 and inhabited by 5 million. Kathmandu was not the reason that I came back here though…

I went to see Rajendra, my trek organizer, in his closet-sized office and paid him for the trek. Rajendra is a very nice man of the same age as me. He is extremely fair in his business dealings. He is a gentleman, never gets angry, always smiles and is very genuine. I really like dealing with him and he is my go-to guy in Nepal. He is a city guy and does not particularly like trekking in the high mountains. His staff is also very genuine and kind. If needed, Rajendra hires a Sherpa climbing guide to support his regular guides. They are all extremely nice and likeable. I have become friends with many of them all over the past decade.

My plan was to do the Manaslu circuit, continue onto the Annapurna circuit and visit the remote Naar and Phu villages. Alternatively, we would skip the Near/Phu and go to Jomsom via the Mesocanto Pass. Manaslu is one of the 8,000m mountains in Nepal as is Annapurna. Both mountains form two distinct massifs that are separated by a deep valley. I had three weeks plus on the trail to make it all happen. I was gone for a month but travel to and from the trailhead ate the remaining days. The Manaslu and Annapurna trails are connected and form one long journey that covers the distance of almost 300km. This long trail is also part of the Great Himalaya Trail.

In order to obtain the permits for this trek, hikers need to travel in a “group”, which is defined as two or more persons. Since I was alone, I needed another person to form a “group”. In order to get the necessary permits, Rajendra paired me with some random German guy who happened to walk into his office and purchased the Manaslu trek as well. It is customary in Nepal to pair random people on a permit just to get the bureaucracy out of the way.

Rajendra, quite enthusiastically informed the German that he also had a permit for Naar and Phu villages for no extra charge since he was on my permit. The German was reluctant to go there and was skeptical about his ability to see it through since he had no tent or any other gear. Rajendra reassured him that he could just sleep in caves and scavenge for food from the locals or the forest and that there would be no problems with this plan. The German was quite scared of this option and visibly shaken (it was funny to watch). The more Rajendra reassured the German, the more reluctant he became suspecting some sort of a scam or attempt to rob or murder him by Kumar and I. The guy obviously did not appreciate that in Nepal, improvising and letting events just happen without prior planning is a part of the local psyche. Winging it is often the Nepali way.

The lack of a detailed plan, inexperience and sometimes complete ignorance of the route and its dangers is very common and widely accepted form of doing business. Independent guides are often farmers on a break from plowing their fields who travel with westerners for a quick buck. Before the trip they are full of confidence and reassure their clients of their vast experience and knowledge. Once in the field, their incompetence and ignorance sometimes has disastrous results (I witnessed it first hand during the Kangchendzonga trek in 2013). It is very important to know the people that one deals with in Nepal and to find a reputable and legitimate agency. I trust Rajendra enough to know exactly what to expect from him, his guides and the crew. Having said that, I also feel that safe trekking requires everyone to be prepared and have some level of training and experience to be self-reliant.

Personally, I like the improvised and unstructured nature of traveling in Nepal. This form of travel allows me to change my plans and to improvise. It also gives me the freedom to stray from the itinerary, which is the opposite to the restrictive nature of group travel. Traveling alone takes this freedom to the limit for me.

The German fellow gave up an opportunity to join us for the drive to Arugat Bazar (the starting point of our trek) the following day by a 4x4 as he was obviously suspicious and scared of us at this point. He opted for an 11 hours bus ride that must have been just horrible. Eventually, I never saw the fellow again and I am not sure if he even went.

October 24, 2011 Arugat Bazar (Monday) 530m

We left Kathmandu early in the morning leaving the traffic and smog behind. The road to Arugat Bazar and the Manaslu region follows the main “highway” in Nepal between Kathmandu and Pokhara. The highway is choked with trucks belching unreal clouds of fumes and pollution. They also overuse their incredibly loud and elaborate-sounding horns. The caravan of brightly colored and decorated trucks snakes its way out of the Kathmandu Valley at 10 km per hour and then slowly descends to another valley along which the highway leads to Pokhara for 180 km. Usually, it takes 10 hours by a local bus to complete this journey (five hours by jeep) due to endless construction and traffic. Fortunately, we turned off the highway quickly and left the traffic behind after about two hours. Our destination was Arguat Bazar, the district capital and the starting point of the Manaslu trek.

The road to Arugat Bazar hardly qualifies as a road. The track is made up of a maze of deep ruts in the red earth. The track dissolves into liquid mud during the rainy season, often impassable, and solidifies in the fall. There were a lot of cars, buses and lorries stuck in the deep mud along the way.

We drove the 40 km distance from the mail highway in 3.5 hours and arrived in Arugat Bazar by 12.30 pm. Arugat Bazar is hot, it is made from concrete and has little charm. We unloaded the jeep and left immediately for our first destination, Soti Kola, that was apparently 3,5 hours of walking away. As soon as we hit the trail, there was a check post and we needed to produce the required permits. I am not sure how Kumar handled the missing German but we went on without any problems.

We walked on a flat trail and it was rather uneventful. We passed small villages with many children asking for balloons, pens or sweets. Obviously this was not a virgin trekking route. I could not wait to leave the lowlands and go to higher elevations. The villages and towns that are accessible by a road have a different feel from the villages that are more remote. The road access makes them more commercial, busy and ultimately soulless. The high mountains seem much cleaner and sane.

There was no road up the valley to the villages above. All supplies have to be brought by people or mules. The mules carry all sorts of supplies up and down the valley. The mules, along with yaks, are also used for trade with China as Manaslu region is basically on the border with Tibet. I would witness this trade higher up the valley. The shops in villages are well stocked with the cargo brought up by the mules from below or from China. A lot of things, especially materials for house construction (lumber, pipes, cables, etc.), are carried up by porters. A porter’s time is worth much less than the mule time. It is very sad to realize that human potential is wasted to such an extent on such menial tasks. I have seen this before in Pakistan and other parts of the world.

October 25 Soti Kola (Tuesday)

Today we run into a large French group (22 persons) also going around Manaslu. Since my crew was blissfully unaware of the route ahead, their guide gave us good tips for rearranging our itinerary to save time. We would combine some sections lower down to maximize the time higher up. We have followed his plan and it worked our quite well.

October 26 and 27, 2011 (Thursday)

We are walking along the valley passing many villages and settlements. Each village has many, many small children. Sometimes all we saw were children looking after children with no adults in sight. On the 27th of October we walked for 7.5 hours. In one of the villages, we bought a chicken after much difficulty of convincing the local lady to sell us one. As we are moving further up the valley of Buri Gandaki, the villages that we are passing through are more traditional in their adherence to the Buddhist traditions and beliefs. Anyone we approached to purchase a chicken knew that we wanted to buy it for food. Since we would kill it, they did not want to sell it to us as they did not want to participate or cause death and suffering of a sentient being. Killing a chicken would result in a negative karma to them and to their village. We finally found a local lady who agreed to sell us one. After much convincing we promised her that we would kill it in another village further up the valley. It was another matter to catch it. She run around the yard for a long time chasing the clever and fast chickens before she eventually got one. Kumar convinced her that killing the chicken in another village would cause the negative karma to beset that village and not her own. Everyone seemed happy with this compromise.

I felt sorry for the chicken but could not stop Kamsing from killing it. I learned that chickens know their way home. They always make it back to the coop for the night. We carried the tied chicken for couple of hours as promised, before we killed it and cooked it. The chicken was stressed out and this affected the quality of the meat that ended up chewy and not good. At the end, it was not worth killing it just like the law of the valley intended.

So far, we walked faster than planned and combined a few days from our itinerary in order to spend the saved time higher up. Nepal’s low valleys seem all the same: hot and humid. Walking in canyon-like deep river gorges, such as this one of Buri Gandaki, can be tedious as there are no views, there is little sun, and walking becomes a slog.

This valley has been very nice though with many spectacular views of waterfalls some of which were quite impressive. Just because we can not see the high mountains, does not mean that they do not tower high above the valley. The numerous waterfalls revealed their existence. In Tatopani there was even a hot spring that allowed for a hair wash after a long hot day. The teahouse in Tatopani was quite something – the celling was so low that I could not stand up. The toilet was also very low, like a cave. I had to squat to enter and remain in that position for the duration of the “visit”.

October 28, 2011 Sama Gaon Friday 3450m

Sama Gaon (or Simigon) is a grim little village that seems to exist in another century. Sadly, the people living here are accustomed to conditions not far off from the animals that they keep in their homes. This is very common in remote settlements along the entire Himalayan chain. There is a general feeling of filth and squalor. Although we are passing many elaborate mani walls and beautifully decorated chortens, it is difficult for me to see much artistic culture in this stone-age lifestyle. How can the people that fight for survival devote time and energy to creating art? The only signs of artistic culture are the mani walls and chortens that were built many years ago and are covered by the patina of time. I wandered who built and carved the beautiful stones? Most likely, they were built by the monks and not the villagers.

On the way to Simigon we stopped in a small monastery that, in sharp contrast to the surrounding villages, did not lack too much in terms of comforts. I suppose that the monetary receives support form outside the valley.

Kamsing, the porter and cook and a great man, specializes in making great momos. Momos are steamed or fried dumplings filled with truly organic vegetables from the villages that we pass along the trail. Kamsing tried to teach me how to make them as the process looked easy. When I tried, it was quite hard!

October 29, 2011 Saturday Samagon 3450m

Last night we camped in a yard of a house belonging to a local family. In the evening, we were invited to sit by the fire in the kitchen. The lady who owns the house was very nice, welcoming and gracious. She had a great smile and happiness in her eyes. I am constantly amazed how little the people here have and how little one needs to exist. Each family usually has a shoddy house and some land to grow their food. All their meagre belongings have a purpose and are used by them each day. They share it all with total strangers like me, who happen to walk by their house. In their homes, there is no room or need for cuties or décor or excess things. By contrast, back home I am surrounded by superfluous material possessions majority of which are not really needed or required for anything. The big difference between our lifestyles that I notices right away is that they can grow their own food which makes them self-sufficient. They eat simple and organic diet. They have the skills to attend to the animals and to take care of their land. This connects them to nature. We have lost this connection and live in isolation from the natural order of things. Of course this is a romanticized and superficial perception but I noticed it right away.

I do not think that I would last here very long. They would have no use for me, as I do not know the skills that are required to live here – not even how to kill a chicken. It is interesting how we all become an extension of our environment and, sometimes, we become imprisoned by it.

During the evening conversation by the kitchen fire, she told us that her sister died recently during child birth. She was not sad or bitter but very accepting and factual about the entire experience. She smiled and seemed at peace with the events that she was describing to us. The people here have an attitude of acceptance and let the fate (karma) decide the events of the day. They do believe in karma and based on this belief, accept whatever comes their way with little protestation. In the villages, there is no access to medical care and the road is a few days of walking away. Sudden medical emergencies, like a complicated delivery of a child, usually end one way. We, on the other hand, attempt to control all aspects of our existence end usually end up disappointed and unhappy when things do not go our way. Surrender and acceptance are rare qualities in the West.

Today was a spectacular day. We had our first view of Manaslu and the entire range ahead of us at the end of the valley. It was very impressive. This 8,000m peak towers above the valley glowing white in the sun. The massive glaciers and iceflows descend all the way to the green fields below.

On the way, we stopped at a large monastery. It is the main Buddhist monastery in the entire region. It is perched on a hill overlooking the fields below. While we were there, the monks and the locals were celebrating the puja ceremony. There were a lot of monks and village folk. Everyone was praying, spinning prayer wheels and singing. It is interesting that mostly old people participate in the prayers. We were told that the young are busy grinding it out in Kathmandu or in the Gulf. This is the curse of poverty in these remote regions. The young leave and the families are broken apart. After the prayers we mingled with the locals, took photos and exchanged addresses. Everyone was very welcoming and friendly. There were no other tourists there.

The trail to Manaslu is like a roller coaster: it undulates up and down with very few flat sections. Each undulation does not seem like a lot but after all the ups and downs, it really adds up. Up 60m down 30m, up 60m again and on and on like a roller coaster it goes.

On this trek we meet only French trekkers so far. Most French do not know or do not want to speak English. According to Kumar, the French are proud of their culture and refuse to speak English even of they know it. Kumar has identified and labeled each nationality. His opinions are based on his experience of working with various people over the years. He attached specific characteristics to each nationality that most define them. Some of his opinions and observations overlap with our perceptions and some are just very funny and interesting! It is interesting how little details can separate one group of people from the other and make them distinct yet underneath we are all the same.

I have not met any single English speaking trekker yet and did not have an opportunity to chat or talk with anyone except my crew. There are a lot of French but they refuse to speak English and stick to themselves. So I usually hang out with my porters and Kumar in the kitchen. We drink tea, talk and laugh. This gives me an opportunity to observe the interaction between the Nepalese and allows me to get to know them a little better. I like them a lot as they are jovial and lively people. They treat each other with friendliness and openness. On the trail, they seem to have instant camaraderie and connection as if they had known each other for years. In contrast to that, the foreigners (like the French I met so far) seem guarded and reserved. The Nepalese I met take life as it comes without much planning for the future or rehashing the past. We on the other hand, seem to live mostly in the past or in the future, seldom in the present moment. They accept their fate while we resit it. They accept their surroundings as they are, while we try to change them and modify them to suit our needs often against the natural laws. I know that this is not the universal truth, but on this trekking trail it was my observation.

In each teahouse and every house, the kitchen is the focal point of the social activity. In the teahouse that we are in now, the kitchen is a transit point for the porters and travellers that pass through this valley. The visitors come by, sit and chat for a while. They have a cup of tea, exchange information about the trail, the weather or other important things in life and then go on their way. It seems like not much has changed in 200 years. When I imagine how traveling used to be in Poland (where I come from) 400 or 500 years ago, I think of this experience.

We are now right under the Manaslu Mountain. Tomorrow we will try to go to the Manaslu basecamp. Apparently, is it a 4-hour hike each way. I am starting to feel the pain in my thighs and butt from long days of walking. We have been walking non-stop since Monday (it is Saturday now). We usually walk for 7 hours each day with good speed. I hope that I can make it over all these passes and the distance – it seems like a lot. If I do, I will have a good sense of accomplishment.

October 30, 2011 Samagon 3450m Manaslu BC 4800m

We started the day in brilliant weather: blue sky and not a cloud. The morning light on Manaslu was brilliant, the sun was illuminating the entire mountain in front of us with deep blue sky as a backdrop.

To get to the basecamp, we walked up an old moraine that is now overgrown with drab and leafless bushes that brushed against us as we laboured up. The basecamp is at an altitude of 4,800m so we ascended 1,350m from the village. The final approach to the basecamp ("BC") is along the crest of an old moraine next to the jagged glacier that flows down from Manaslu. Soon after we got to the BC, the clouds started to fill up the valley below from the direction of where we came from. To the east, we could see all the way to the Ganesh Himal and all the high peaks in the Manaslu Range. A large green lake glittered in the valley below. It was a fantastic view. The glaciers and ice surrounding us on all sides were very spectacular.

The wind picked up and we stayed as long as we could before the clouds moved in to obscure the view completely. The BC is on the moraine in front of the Manaslu northeasterly face marked by chortens and prayer flags. There were no tents in the BC as the main climbing season is in the spring. After taking many photos, we descended in the clouds and the rest of the day was overcast.

October 31, Samdo 3860m Larkya La BC 4460m

The day was overcast with low clouds obscuring any views of Manaslu or the surrounding mountains. On the way to Samdo, we run into a teacher who was also a monk with a group of rowdy kids that were more than willing to pose for photos and joke around.

In Samdo we stopped for lunch in the only teashop. The food was prepared on the floor while everyone was walking around it. The owner did not, of course, wash her hands (I am yet to see any of the cooks to wash their hands). The overall process of food preparation was very slow. They chat, take breaks, look after the kids and do whatever needs to be done at that moment. I waited for two hours for a simple meal and watching her do it was almost painful. No one was in any rush and frankly, neither were we.

Sometimes I think that the locals look at us, the white folk, with a mixture of curiosity, pity, contempt and envy. They pity our rushed, anxious and scheduled ways of doing things, they do not quite get us so they are curious about us. Since we do not follow the teaching of Buddha they look down on us with sorrow (we seem to be confused about the true nature of things). They are envious of our stuff and money and maybe of our clean hands. They do not understand our preoccupation with planning and worrying about the future that we do not know or can even influence as many things are outside our control. They pity our ignorance about the Karma and our inability to accept the impermanence of things. They also seem very set in their ways and changing those ways may be very difficult or impossible for them. Our interaction with each other is limited to the exchange of rupees for food or service. It is really a shame because we could both learn from one another.

We as the visitors do not have much chance to make any genuine contact. We meet in the commercial realm, they have something to sell and wee need things to buy. This is where our cultural interaction starts and ends, all superficial niceness aside. The Nepalese are somewhat reserved and do not express their opinions freely. When one of the locals gets drunk on rakshi, then perhaps some truth comes out. Today, a porter got drunk on rakshi and started to make some statements that made my guys very uncomfortable. Kumar did not want to share the drunk’s insights but I sensed that they were rather derogatory towards the tourists. On this trip, I have a lot of time to observe and contemplate these things.

Samdo is the last village in Nepal before the border with Tibet. Caravans of mules, loaded up with Nepalese crafts, semi precious stones and other goods make their way to the bazar on the other side of the border. The money obtained from selling all the imported stuff to the Chinese is then used to buy the Chinese goods that are resold in Nepal. There are no border controls by the Nepalese and the Chinese turn the blind eye to this cross border commerce. It seems that the trade is quite active and good for the locals. It obviously dates back hundreds of years.

Our next objective was the Larkya La (Pass). This pass connects the Manaslu and Annapurna regions. After we left Samdo after lunch, we continued our approach to the Larkya La basecamp. The views cleared up in the afternoon and we could see the northern aspect of the Manaslu range. It was very spectacular. Across the valley from where we were, a row of high mountains towered over a small glacier. The higher peaks of the Manaslu proper filled the background. We arrived at the collection of stone huts that were the Larkya La Pass basecamp at the altitude 4,460m in late afternoon.

The weather deteriorated in the evening. It snowed heavily all night and it did not look like we would be able to cross the pass the following day. I thought that maybe I had some curse for these passes. In 2007, we had horrible snow storm on the pass to Mt Kailash, last year, we had really bad weather on the Teshi Labtsa Pass (right on the pass crossing day) and this year it is the same story again.

November 1, 2011 Larkya La Pass 5,135m

Today we crossed the Larkya La Pass at 5,135m. All night, before the crossing, the snow was falling heavily. It was a total whiteout. There was another French group in the basecamp with us, and they left at 4 or 5 am. If the weather remained bad, we would have waited at the basecamp. We eventually left at 7am after the weather cleared up a little offering us hope that the storm would pass.

I had a bad night sleep at the basecamp at 4,400m. The room in the stone shelter was a windowless cell with wooden beds. Considering the remoteness of the location and elevation, it is still a palace compared to sleeping in a tent. It was cold and drafty but it beats camping in the snowstorm. The building is made from loose stones that were just piled up on top of one another without any insulation between them. Consequently, the wind just blows right through (I think that a tent offers better wind protection but the flapping makes sleeping difficult anyway).

I woke up at 10pm and could not sleep until 3 am tossing and turning in the sleeping bag. At first light, I had a quick breakfast consisting of a greasy omelet. As we were eating breakfast, the snow was still falling and we were not quite sure whether we should go or not. It was overcast and the aura did not look promising. At dawn, it cleared up slightly so we decided to leave. As we progressed up, the visibility improved and we could see great snowy peaks through the swirling clouds. The entire pass was snow covered and it made it look and feel very high and alpine. We could see fresh snow avalanches coming down from the Larkya Peak that towers above the pass. The views to the east were ok but the west was in a total whiteout. As soon as we reached the pass the cold wind started to blow and we could see absolutely nothing to the west of us.

After a quick group photo we descended quickly, passing the French group along the way. The descent was very slippery down a frozen moraine, frozen mud and rocks. I had to concentrate fully to maintain balance on the iced rocks. I managed to bend one of my walking sticks to halt falling after I slipped on the frozen mud. The walk to the campsite of Bimitang was very long and gloomy. We walked in the fog whiteout without any views. Once, the Phungi Peak managed to show its very steep face somewhere high between the angry clouds. It was a pity, as I knew that all around us in the fog there were spectacular peaks. At this elevation, the views would have been fantastic. We arrived at the camp around 2 pm.

Looking west from Larkya Pass

November 2, 2011 Bimitang 3,850m

After crossing the pass I felt like quitting and going back to Kathmandu. I was disappointed about the weather. This was a natural exit point as the Manaslu trail connects to the Annapurna trail near here. The weather was not good and it had not been good for the duration of this trek so far. It is interesting how the weather influences how I feel. I think that my sour mood was caused by a combination of the weather and the lack of companion to whom I could complain to about the weather.

The following day started clear and brilliant. Once the sun came out I regained my enthusiasm. I decided to stay put in Bimtang for a day and explore the area and to take advantage of the sun.

Bimitang consists of two stone shelters and a few others under construction. The room is very drafty with stones slapped together with large gaps between them. This makes for a chilly night. The outhouse is literally full of shit and overflowing. Consequently, the hill of the moraine behind the settlement serves as the communal toilet. In addition to the normal toilet business, the hill is full of broken glass from beer and alcohol bottles. The porters must hold parties here to celebrate crossing the pass and consume large quantities of local spirits. The locals knew how to build a hotel and a restaurant but forgot about a proper toilet.

The kitchen in the teahouse is again the center of activity here. Since I am alone, I hang out with the porters and guides in the kitchen. It is a smoky and dark place. Everyone is squatting by the wood stove. The place is very smoky because the chimney from the stove ends inside the room and does not vent to the outside. The source of the fire is from local wood, which is quite scarce. The fire stove is also used for cooking. There are a lot of folk coming and going all day jabbering in Nepali. They usually have a glass of rakshi (local alcoholic drink) and a smoke as they squat by the fire to warm up their cold hands. There are very few other trekkers though.

It is unfortunate that I do not understand anything, as it would be interesting to listen to stories about their experiences on the trails and life general. Kumar (Bimbadur) told me that his house in the village where he is from is like this kitchen, the center of activity. Since there is no radio, books, newspapers or television in the village, people congregate to talk and entertain each other with stories.

In the teahouse, they cook in almost total darkness. It is difficult to believe that they can make anything without seeing. The selection of food here is rather simple mainly consisting of rice, some local greens and tea. The Nepalese eat dhal bat everyday, all the time. They do not add any variety to their diet. The variety is expensive and they do not have this luxury.

Today, November 2, we went for an exploratory hike to the head of the glacier to hopefully salvage some views that we missed the day before while crossing the pass. When I got up in the morning to see the weather, it was still overcast and gloomy at 6am. When the sun came out, the clouds parted and the magnificent panorama of huge white and wild mountains and glaciers revealed itself to us. I decided to stay here for the day and take advantage of being here.

First we had to cross the glacier to the other side. The moraine close to our teahouse was filled with garbage and glass. The glacier was covered with loose boulders that made walking across tricky. The other side of the glacier had a steep moraine blocking the exit. The moraine had large boulders and rocks hanging by a thread ready to fall at any instant. I do not like walking or climbing the moraines for the fear of dislodging the rocks. We climbed up the moraine to the ablation valley on the other side. There was a trail there and we followed it up the valley. At what seemed like the end of the trail, we climbed back to the top of the moraine. The altitude was 4,100m and the climbing was surprisingly tiring. My pack seemed quite heavy although I only had my camera and water. The view from this point was great, we could see across the glacier to the pass we crossed the day before. At the head of the glacier, a wall of large peaks dominated the view. One mountain in particular was very striking, a pointy triangular tooth that looked like a small version of the famous Cerro Tore in Argentina. It must be more than 6,000m high perhaps even 7,000m. Behind us, a magnificent and huge west face of Manaslu dropped steeply to the valley below in a 4,500m sweep of spectacular icefalls. The peak next to it, Phungi is also very steep and spectacular. Kumar thought that it was Annapurna 2 when he saw it through the clouds while descending from the Larkya Pass.

Soon though, the clouds started to move up the glacier towards us. Since it was still early in the day, the sun was directly behind Manaslu making photography of the west face difficult. The clouds moved quickly, and around 10 or 11 am obscured the view. Since it is the west facing face, the good light for photos is in the afternoon. What a spectacular face though. It is hard to see how a photograph can do justice to such a magnificent view. Standing under the west face of Manaslu makes an impression on the observer and exemplifies why the Himalaya are so spectacular. I think that Manaslu is especially spectacular as it is so isolated from the other high peaks as compared to the high mountains of the Khumbu. The entire Manaslu range stands on its own. The Manaslu Himal is separated from the Ganesh Himal by the gorge of Buri Gandaki that we just walked up. On the west side there is another gorge where we will drop into tomorrow to link up with the Annapurna Circuit trail.

Manaslu is so high and large that it most likely generates its own weather. We had very sketchy weather on the Manaslu trek. We had overcast days with heavy cloud cover. We also had a lot of rain and snow. We are now sitting in Bimitang on the west side of Manaslu at the altitude of 3,750m engulfed in fog. It is damp with no visibility. It is also snowing lightly again. All in all we had maybe 4/5 hours of sunny weather today.

We have made a decision to skip the Nar and Phu and Kang La section of the trail and instead go to Jomsom via Tilicho Lake and Mesocanto Pass. The regular route of the Annapurna Circuit is via the Thorong La Pass, which is 5,400m high and, on average, 300 people a day go over it. Mesocanto La and Tilicho Lake on the other hand, have fewer visitors and the route to the pass travels along the Great Barrier (a continuous wall of high glaciated mountains forming a northern boundary of the Annapurna Range) offering great views. The pass is considered more difficult and steep and this is the reason why it is not used frequently by trekkers. It is also remote and often blocked by snow and ice. Due to its steepness, snow presents an avalanche danger and ice can make it impassable. The route to the pass also requires 3 nights of camping at 5,000m+ altitude. Most trekkers doing the Annapurna Circuit are not equipped with camping and climbing gear to traverse the Mesocanto Pass. The area is therefore not touristy, in sharp contrast to the rest of the Annapurna Circuit.

I hope that we will be able to do it. I do feel the last 10 days of non-stop walking in my bones and I hope that I have enough energy to complete this trek. Kumar estimated that we walked 150/160 km from Arugat so far. We actually walked 223.22 km from Arugat to Darapani in 11 days.

Today I had some rakshi with my crew to beat the weather blues. Rakshi is a mild wine made from barley and similar to sake in taste. I also had some good fresh radish. The radish is white long root vegetable that can be eaten raw, fried or pickled (with chili powder). The pickled radish is good with rakshi. I was much happier after the rakshi!

It would be very interesting to cross the Himalayas between Nepal and Tibet with the caravan from Samdo. The caravan travels to the market in Tibet in two days and brings back alcohol, beer, cleaning products and cheep Chinese clothing. In Tibet, they sell trinkets from Kathmandu, turquoise from Taiwan and silver. The caravan uses horses and yaks to carry the goods. The horses have a tough life here. They are left in the cold and snow, have scars and open sores from the bags they carry. Some of the wounds look fresh and open. There are no medicines for the animals or vets to attend to them. The horses also do not seem to be well fed as I witnessed them eating garbage (including plastic bags). But considering the living conditions of the people, who has the time to think about the animals?

November 3, 2011, Darapani

Today we arrived in Darapani, which represents the end of the Manaslu section of the trip. It was a long, long walk from Bimitang to Darapani covering the distance of 25 km. It seemed like the longest day of the trip so far. We walked in the fog, which I find depressing, as there are no views. We are on the Annapurna section now. The village is more developed and there are more tourists. We will go to Chame tomorrow, which is supposed to be an easy day.

I took a bucket shower (first one in 11 days). In the teahouse, the room was infested with large spiders that Kamsing killed quite efficiently at my desperate request. I wander if it will rain now for the next 5 days.

November 4, 2011 Darapani to Chame.

Yesterday we walked from Darapani to Chame on the Annapurna Trail. Hordes of people – looked like over 350 in places. It was quite a shock after the serenity of the Manaslu trail. There were lines of people on the trail especially when going uphill. At one point there was person to person line on the trail. It was all very unpleasant. The people in the line were all white folk: English, French, German, Polish, Russian, and Spanish. The whole of Europe was here. A long line of European trekkers must look like a giant centipede with 100 trekking poles that look like legs moving in unison.

The walk was easy and relatively short. Kumar purchased a chicken that was then made into a stew. This time the purchase was without any drama. We had a 3-hour lunch break. After lunch the walk was again in the fog, no views. We heard on the radio that in Lukla, 2,000 people are stranded at the small airport again, the same happened last year. Hotels have no food, the banks have no cash. There must be scenes of pandemonium there. In the evening we watched Bond – Diamonds are Forever with the porters. It seems that this year the weather is poor all over Nepal. This resulted in poor weather on the Manaslu trek as well. Tomorrow we continue on to Pisang village on the Annapurna Circuit trail.

November 5, 2011 Chame – Pisang

The walk up to Pisang was through a nice pine forest. Easy and uneventful. The weather cleared up after Pisang and the scenery changed a lot. In order to get a room in Pisang (which is quite difficult on this section of the trek) I was instructed by Kumar to lie that I was climbing Chulu Peak (I am not sure why?). The hotel owners are reluctant to give out rooms to singles and tell me that they are full (which is not true). In Pisang, the cook from the teahouse got really drunk and gave us great performance in the evening. Apparently he cooked on one of the Kamerlander’s expeditions - everyone has a story here. The route from upper Pisang follows a high cliff overlooking the valley below. Across, is Annapurna 2 and to the west, the view extends to Manang and Tilicho Lake area, which is our next objective. The route we will be following now is along the north side of the Annapurna range with spectacular views. The area looks dry and desert-like, reminiscent of Tibet.

November 6, 2011 Pisang - Barga – Manang

We arrived in the village of Barga, which is located 2 km before Manang. The village is located on a dramatic rocky cliff. The houses climb up the rocky escarpment with the gompa situated in the middle. It seemed deserted though with no people in sight.

We moved on to Manang, which is located in front of Gangapurna, a 7,000m mountain in the middle of the Annapurna range. We had a tough time finding a room in Manang as the village was very busy (being the last stop before the Thorong Pass) and the proprietors did not favor single travelers. The owners of teahouses here are shrewd businessman and businesswomen who have dollar signs in their eyes. They seem to be very experienced in separating tourists from their cash and give the locals (my crew) very few concessions. Kumar judges how badly commercialized the trail is by how much they charge him for a cup of tea. A free cup of tea indicates a good value and low level of commercial development. When he has to pay for tea more than in Kathmandu, he feels ripped off and the locals are no good. Everest region is the worst in his opinion.

We did manage to find a room though that we all shared. Manang is a crowded place geared up to service masses traversing the Annapurna Circuit trek. It is build up and soulless (at least the new part). Grey concrete hotels dominate the landscape.

We are moving on from there and leaving the main Annapurna Circuit trail to go to Jomsom over the Mesocanto La Pass. After walking on this trail, I would not come to Nepal to do the Annapurna Circuit. It is too crowded, very commercialized, devoid of local culture and lacks the high alpine experience. It is good to cross it off the list though.

The route to Mesocanto La follows the flat riverbed at first with good views back to the village of Manang where we spent the previous night. It also offers spectacular view of the north side of Gangapurna with its steep fluted snowy slopes. The route then crosses the hanging bridge and starts ascending towards the Tilicho Lake. The area is very dry. The riverbed is dry and arid. We are on the north side of the Himalaya range so the rainfall is much lower than on the south side, which is very lush and green. The 8,000m high Annapurna range blocks the annual monsoon rains with very little moisture making it into the northern slopes.

Along the way, we crossed very steep and gnarly scree slopes that drop off to the river 1,000m below. This section gave Kumar and the guys a scare, as they felt that the trail was loose and exposed. The scenery was outstanding and it improved the higher we got. The slope we walked on was punctuated by tall sandstone pinnacles and wired rock formations. It looked as the weather had finally improved and we left the rain and snow behind in the Manaslu region.

We arrived at the Tilicho Tal basecamp at 4,140m. The camp was very cold, as by the time we got there, the sun has already disappeared behind the mountains. In front of us, the Rock Noir (a prominent mountain in the Annapurna Range) rises to above 7,000m. We could make out the very top of Annapurna 1 at the end of a ridge extending from the Rock Noir. (I would have a good view of this mountain from a helicopter in 2017 while visiting the Annapurna Sanctuary - see the 2017 year).

The wall of ice and snow behind us was glowing brightly in the setting sun. We set up the camp, had a juniper fire and stomped around in the cold. When we run out of things to burn, it was time for a cold sleep in the tent at 6 pm. I was wandering, what to do for all the hours between sunset at 6pm and the true bedtime? This is the worst thing about camping at high altitudes among the peaks. It gets really cold after the sun sets and 6 pm is not the time to go to bed.

November 7, 2011 Tilicho Lake – Tilicho Tal Kharka 4,949m

The approach to the lake was very dramatic. The trail ascends diagonally along a bare slope with dramatic view all the way back to Manaslu Range. The peaks of the Annapurna Range came into view as we climbed higher. We could see Gangapurna, Annapurna 3 and Rock Noir - all the peaks of the Annapurna Range over 7,000m. As we walked up the trail towards the Tilicho lake, the Great Barrier appeared immediately in front of us. The dramatic icefalls and cliffs of the Great Barrier were so close that it seemed that they could be climbed in no time (of course it was very deceiving).

The Tilicho Lake is very beautiful. It is flanked by the wall of icy ridges of the Great Barrier on the south side. The area looks like Antarctica. The icefalls descend all the way to the green lake below with chunks of glacial ice breaking off into the lake. The place is cold and windy. We had brilliant blue sky which bode well for the crossing of the Mesocanto Pass. We stopped briefly for tea at the lonely teahouse by the lake. Most people who venture out here return to Manang (or teahouses below) the same day. It is not a busy area and definitely it is a big contrast to the crowded Annapurna Circuit and the Throng La Pass.

We found a nice campsite on the north side of the lake directly across the Great Barrier. The sun hid behind the peaks around 3.30 pm making the light for photos too dark. Once the sun was gone it got quite cold. The altitude is close to 5,000m here and the sky was clear which made the temperature fall even further. It got so cold after the sunset that Kumar and the crew did not sleep at all during the night. I usually take a Nalgene bottle filled with boiling hot water and put it in the sleeping bag. When it is really cold I take two. This was a two hot water bottle night. Unfortunately Kumar, Kamsing and Suri had two sleeping bags for the 3 of them. They tried to share it but it did not work so well.

Tomorrow is Mesocanto La crossing. I am anxious and eager to get this journey finished. It has been a long distance and it feels like a long time. In retrospect I have seen so much, a lot of varied landscapes, famous mountains and I added another 300 km to my Himalayan trekking resume and my goal to travel the Great Himalaya Trail in its entirety.

It is 6.30pm and I am in the sleeping bag already. It is dark and cold outside at 4,920m although it is a full moon night (the moon has not appeared yet from behind the Annapurna Range). What would I do at home at 6.30pm? Definitely not sleep. Kumar, Kamsing and Suri sleep together for warmth. They have two poorly insulated sleeping bags between the three of them and only two mats. They have no spare clothing; their boots are falling apart and have holes in them. Yet they never complain, not even once and they always smile.

November 8, 2011 Mesocanto Pass 5,350m

We got up early at 5.30 am because of the intense cold. It was still dark and clear as the sun did not rise until 6.30 am. The tent had a lot of frost inside from condensation. The peaks across the lake, illuminated by the full moon, looked eerie. The silver light of the moon projected on the white peaks was reflected in the still water of the lake like in a giant mirror.

After a cup of hot noodle soup we left the campsite for the pass that was a long way away. I was anxious about the pass due to its reputation as difficult, steep and technical. It is not a very well frequented area so there is no formal trail. It turns out that the Mesocanto Pass is actually a series of three passes connected by a high plateau. We started walking around 7 am and made it to the first pass at 5,350m around 9 am. The weather was clear and brilliant, probably the payback for many days of rain and snow we had on the Manaslu side. The rising sun illuminated the Great Barrier and the lake. Behind Rock Noir, the summit of Annapurna 1 was now visible. The scenery was beyond spectacular.

The walk from the first pass at 5,350m to the actual Mesocanto Pass is very long. The entire way is above 5,000 meters. We made it to the second pass at 5,100m with a great view of Tilicho Peak and Nigrili North. The bulk of Dhaulagiri also came into view. We were basically walking around the Tilicho Lake at above 5,000m and now had views to the peaks on the east side of the lake: Gangapurna, Annapurna 3 and Annapurna 2. We arrived at the third pass at 5,100m shortly thereafter. It would be terrible to encounter a snowstorm here. The exposed and high plateau between the passes would make the route finding quite tricky.

The mighty Mesocanto Pass was right there in front of me. The views from the pass to the lake and to Dhaulagiri and Kali Gandaki valley were spectacular. We had completely clear weather and no wind. We could see the mountain range across the valley with the Dhampus Peak and the Dhampus Pass on the horizon. The Mesocanto pass itself is marked with a very sharp (horn like) small rocky peak. It is clearly visible from a long way away, which makes it easy to pinpoint the location of the pass. I could see it from the Dhampus Pass in 2016 during the Dhaulagiri Trek.

The descent route looked very steep indeed. The pass lived up to its reputation. Now I did understand why this pass has such a fearsome reputation and is considered difficult. The descent route is basically a steep snow chute with steep rocks on both sides. The chute was full of snow and ice. One slip would send a person all the way down for a 300m ride to the rocks below. For a moment I considered going back to the Mesocanto North Pass, which was supposed to be easier.

Kumar and Kamsing did not seem too concerned and started going down. The descent was quite exposed with steep drop-offs all around. The rocks were thankfully clear of snow and ice and there was no wind. We descended very carefully without a rope. Suri slipped a few times as he has the least mountaineering experience between us. The lack of proper boots did not help either. Sometimes I feel that the Nepalese just wing it hoping for the best. In case of a serious weather, accident or altitude issues they could just perish like the porters the year before on Teshi Labtsa Pass.

We descended to the flatter ground and set up camp on a green Kharka (grass pasture) with a lot of yaks. The yaks would meander between tents all day and night. It was strange having a car sized cow with sharp horns snorting right next to me while lying inside the tent.

This is the final night on the trek. We are camping in front of the Kali Gandaki Valley with Dhaulagiri clearly dominating the view in front of us. When I asked Kumar if the Dhaulagiri trek would be worth the effort, he said that I already saw it so why bother? Dhaulagiri looked large and prominent from our camp. We had a spectacular sunset and a sunrise on it.

It is only 5 hours walking time to Jomsom from here. I am happy to have done the Mesocanto La variant instead of the Kang La Pass and Naar and Phu villages. This pass was a true mountain experience with camping and it took us away from the Annapurna circus. The day number 18 of walking is tomorrow and it feels like it has been a long way from Arugat (although it is only 18 days!). Looking at Dhaulagiri it looks so alone and high dominating the sky like the king of mountains. I was thinking of Piotr Morawski and his tragic story of his death that played out in the public eye. It is a lonely place to die. I would see his memorial on the French Pass in 2017.

November 9, 2011 Jomsom 2,743m

The walk down was tiring even though it was only 3-4 hours long. We walked for almost 300 km (or more, as it is hard to measure distances here. Kumar thinks it was 300 km) in 18 days. We climbed 12,585m and descended 11,800m along all the ups and downs of the trail. This was the longest trek that I have done in Nepal.

Dhaulagiri and its ice falls dominated the view like the king of mountains all the way to Jomsom. Jomsom is a typical Nepali dumpy and dry truck stop with hotels such as Dancing Yak or The Meaning of OM. It has some shops selling Tibetan trinkets and Marfa apple brandy. The natural setting of the village is very spectacular with the Annapurna range on one side and Dhaulagiri range on the other. I am sure that being the gateway to Mustang, there are a lot of interesting things to see around here (such as the village of Marfa with its large gompa). It will have to wait for another day though as I am too tired of walking and of taking photos.

The trip has come to the end not only time-wise but also in terms of my energy and ability to absorb more stimulation. I have enjoyed this tip a lot despite my feelings of indifference very early on and disappointment with the weather in the Manaslu region.

At the start of this trek, I was curious whether by being alone, I would have some revelations, insights or deep thoughts. I have not however, realized any great insights in terms of thoughts or profound revelations. The change and impact have been more sublime. At the end, I did feel very at ease, relaxed without any anxieties or anger. The experience has heightened my sensitivity to the beauty of nature, the kindness of the people and my good fortune for being here. The nature has cleared me (although temporarily) from my attachments to some of the artificial aspects of life back home. It was like hitting a reset button on a computer, a spiritual cleanse. It killed the proverbial rat that has to be fed constantly back home. I felt more laid back and able to surrender to whatever was coming my way. The rat was dead (or asleep). It felt like I was stripped down to the basic components that resonate with nature around me. The layers of my armor, needed for the life in the artificial world back home, have been stripped away exposing the socket through which the connection with something greater could be made. I think that this feeling was heightened because I was alone, I had time to quiet my internal monologue and just listen to the silence around me. I surrendered to the process of walking and to my companions. Subconsciously, I surrendered to this process without even realizing it.

I am ready to go home but feel no anxiety about the things waiting for me there. I enjoyed traveling alone and at the end I did not miss the company of other westerners. Deep inside I know that it was a good decision to come here and walk all this way. It was a great opportunity to level myself and experience a separation from my usual travel companions. In retrospect the feelings of anxiety and attachment to the things back home dissolved over the last 18 days. It is amazing how much 18 days can change in one’s perspective. I also learned a lot about the Nepalese through my discussions with Kumar. I had an opportunity to observe and just listen.

I mailed the postcard of Mt. Manaslu with Mt. Manaslu stamp from Jomsom. I am happy to have walked so far and to have crossed two high passes (including a difficult one) in such a short time.

These trips allow me to gain some distance from the things back home. They allow me to look at things from a different perspective. Perhaps this perspective increases my ability for appreciating what I have? Back home, being in the middle of it all, it is hard to gain distance and focus on what is truly important. It is difficult to see the irrelevant and superficial for what they are. I enjoy the simple life on the trail with no expectations just taking each moment as it comes. I give up the control of the process and do not expect the outcome to go my way. I think that I learned from my Nepalese companions that there could be another way of looking at life, at the future and our influence over the flow of events around us. Perhaps the liberation that came from giving up my desire to control everything around me, was the most valuable revelation I had on this trip and on other trips in the Nepal Himalaya.

Since these experiences are reinforced by each consecutive trip, this feeling becomes more permanent and is not as fleeting as if I had this experience only once.

I felt good, happy and ready for another cup of lemon tea.

Manaslu Circuit, Annapurna Circuit Photos

Thanks to Kumar, Rajendra, Kam and Suri from www.mountainsunvalley.com. I did this trip alone with my Nepali friends. We had a great time and it was a fantastic adventure!

Manaslu from space.

The Manaslu Range

Himal Chuli

Himal Chuli on the right

Manaslu Range

Manaslu Range

Manaslu 8,153m from the south from the KTM - DOH flight

Ganesh Himal from the south from KTM - DOH flight

It was about then when I started to think of doing the whole trail.

Walking up the steep trail in the Bhuri Gahandaki Valley.

In the Bhuri Ghandaki Valley

Bhuri Ghandaki Valley

Bhuri Ghandaki and Khutang Himal on the horizon

Lapuchun Mountain 5,990m and the valley leading to Tsum.

Ganesh Himal

Village of Namrung

Namrung Village

Namrung Village

First view of Manaslu from Lho Village

Lho Village

The monastery was built by the Japanese who have a special connection to Manaslu.

Manaslu

Peak 29 7871m

Approach to Manaslu basecamp - looking towards the Ganesh Himal and down the Bhudi Ghandaki Valley

Ganesh Himal in the distance

Ganesh Himal

Manaslu basecamp

Lower slopes of Manaslu North

Ganesh Himal

Manaslu Basecamp

Manaslu and Manaslu Basecamp

Looking north across the valley from the Manslu Basecamp

A local teacher on an excursion with his students.

On the way to the Larkya Pass

Looking at the Manaslu massif from the north.

Syanche Glacier and north side of Manaslu.

Naka Peak and Syache Glacier. Manaslu mastiff from the north

Dharmasala - Larkya Pass basecamp at 4,500m at sunrise. We got snowed at and the entire world turned white overnight.

Clearing storm clouds on the approach to the Larkya Pass.

Larkya Peak North 6,249m in the vicinity of the Larkya Pass.

Larkya Peak 6,616m and Larkya North Peak

Larkya Peak 6,616m

Larkya North Peak

Approach to Larkya Pass

Larkya Pass 5,100m

Looking back to where we came from from the top of Larkya Pass at 5,100m

At the pass

Larkya Pass: Kumar, Kam, me and Suri at 5,100m

Panbari Himal on the west side of the Larkya Pass

Bimthang

Namjung 7,140m from Bimthang

Namjung onthe right 7,140m

Namjung 7,140m

Phungi 6,738m

Phungi 6,738m

Panbari 6,905m and Panbari Himal

Panbari 6,905m

Manaslu and Tchoche Glacier

West face of Manaslu and Peak 29 on the right

Manaslu west face

Summit Plateau of Manaslu

Phungi 6,738

Manaslu from the west

Hanging out in the tea house in Bimthang

Bimthang, Panbari Mountain (right) and Nemjung (centre)

Manaslu massif from the west

Manaslu from the west

Manaslu’s West Face

Upper Pisang

North side of Annapurna III

Annapurna III in the distance

Annapurna III above Pisang

Annapurna III

Near Barga Village

Village of Barga

Barga and Annapurna II

Annapurna Circuit via Mesocanto Pass Photos

The Great Barrier, Tilicho Lake, Rock Noir (on the left) and Annapurna I (far ridge)

Fore-summit of Annapurna II from Upper Pisang

Annapurna III

A friendly lady in the Upper Pisang Village

Upper Pisang Village

Upper Pisang Village

Annapurna III

Newal with Tilicho Peak in the distance

Near Newal village

The village of Barga.

Barga and Annapurna II

Annapurna II and Annapurna IV

The east ridge of Annapurna II

Annapurna III and Gangapurna from Manang

The village of Manang

Gangapurna

Manaslu in the distance

The trail to Tilicho Lake and the Tilicho Peak in the distance

Peak 29 in the Manslu Himal

Gangapurna

Roc Noir and the ridge to Annapurna I

Roc Noir and Annapurna I

The approach to Tilicho Lake. The white mountains on the left are the Chulu Peaks.

Pisang Peak on the right and the Himlung group on the right. The Kangla Pass is in the centre.

Manaslu from the approach to the Tilicho Lake. We came from behind Manaslu.

The Great Barrier

Rock Noir and the Great Barrier

Tilicho Lake - the highest lake in the world at 4,919m.

Tilicho Lake

Tilicho Lake is located at an altitude of 4,919m. It is the highest lake int he world.

Beautiful Tilicho Lake and the Great Barrier

The Great Barrier

Tilocho Lake, the highest lake in the world.

Tilicho Lake

From the left: Roc Noir, Annapurna I, Great Barrier and the Tilicho Lake

The first pass of the two passes on the Meosocanto area

Mesocanto Pass and the mountains of the Dhaulagiri Himal

Long traverse to the Mesocanto Pass with Dhaulagiri on the left.

Nilgiri Peak 7,061m and Dhaulagiri I

Dhaulagiri I from the way to the Mesocanto Pass

Looking back from Mesocanto Pass at the Manaslu Himal (Peak 29 on the left) and the Annapurna Himal (Annapurna II on the right)

Nilgiri Peak 7,061m in the Annapurna Himal

Tilicho Peak ridge and lower slopes

The Long traverse to the Mesocanto Pass with fabulous views along the way. Dhaulagiri dominates the horizon.

Gangapurna and Tilicho Lake

Nearing the Mesocanto Pass

Mesocanto Pass and Dhaulagiri I

Mesocanto Pass and Tukche Peak behind

Looking down from Mesocanto Pass

The descent from Mesocanto Pass.

Descent from Mesocanto Pass

The steep slope leading to Mesocanto Pass from the west.

From left: Dhaulagiri I, Tukche Peak, Dhampus Pass, Jomsom

Dhaulagiri I

Looking across Kali Gandaki Valley with Jomsom below

Dhampus Pass

Tukche Peak next to the Dhampus Pass

Dhaulagiri I and the Tukche Peak

Mesocanto Pass from Dhampus Pass

Mesocanto Pass closeup from Dhampus Pass. You can see the incline of the slope down from the pass.

The valley of Kali Ghandaki, Thorong La (right not he horizon)and Mesocanto Pass )left not he horizon) from Dhampus Pass. Jomsom is on the left in the valley below.

Approaching Jomsom with Dhaulagiri on the left.

Kumar, me, Kam and Suri in Jomsom at the end of our journey.

Rolwaling Valley and Teshi Labtsa photos

Thanks to Rajendra and Kumar from www.mountainsunvalley.com for organizing and running this trip. We were all very happy with the outcome!

Rowaling Valley from the air. From Left to Right: Gaurisankar, Menlungtse, Kang Nachugo, the peaks of Rowaling. Our route followed this range from left to right.

Beautiful Gauri Sankar

Menlungtse in Tibet with Cho Oyu Behind

Menlungtse

Menlungtse and Rowaling Valley

Rowaling, Teshi Labtsa and Panchermo

Rowaling

Rowaling with the Cho Oyu massif behind

Rowaling trekking map

Gauri Sankar

Menlungtse in Tibet

GauriSankar

Beding

The man who lost all of his fingers on Manaslu

Beding

Drainage Ri

Gauri Sankar north face

The Rowaling Valley and Jugal Himal on the horizon. The Jugal Himal separates Rowaling from the Langtang region and it is located in China. It is not possible to cross from Rowaling to Langtang via Jugal and the GHT requires a long detour south and then back north to the Langtang.

Jugal Himal between Rowaling and Langtang regions. The mountains on the horizon are located in Tibet, China.

Tsoboye and Tso Rolpa Lake

The head of the Rowaling Glacier

Kang Nachugo and Tso Rolpa Lake

A view of the valley from Sunder Peak 5368m

Rolwaling Valley and Teshi Labtsa Trip Summary

October 21, 2010 Kathmandu - Dolakha 1,000m

David, Tony and I left for Dolakha, the starting point of the trek the day after arriving in Kathmandu in a small bus that Rajendra rented for all of us. We had a lot of gear and a large crew: Kumar the guide, porters, cooks and us. We knew Kumar from our 2009 Langtang trek. He is a great guide with a good sense of humour and perpetual smile on his face. We also had the same two porters (among others) from our 2009 trip: Kamsing and Suri. The drive was 7 hours long broken by a lunch stop in a spot that we knew from eben earlier visit back in 1996. The town where we stopped for lunch was very busy and noisy. The market and the streets were lined up with vendors selling Chinese goods. We had lunch at a very dirty restaurant serving local food. I did not want to risk getting sick at the beginning of the trip so I decided to pass on lunch. After lunch, during the drive, one of the young porters puked his guts out on a particularly twisty part of the road. The puke landed right in front of me and stank up the entire bus.

We arrived in Dolaka and set up our tent on the edge of town by the busy road. The tent bacame an instant focal point for the local kids that were attracted to the white guys like bees to honey. It was October 21, my 40th birthday. I had a bottle of a surprisingly good Indian wine that we shared in the evening while relaxing by our tents. Although I felt sorry for myself to be turning the big 40, I could not imagine a better way to spend it than hiking in the Himalayas.

October 22, 23, 24, 25 2010 Dolakha – Singati Bazar 950m – Suri Dobhan 1,030m – Gonggar 1,440m

The trek started in the village of Dolaka with a 900m descent to the river flowing from Tibet down a deep., narrow valley between Langtang Himal and massif of a large mountain named GauriSankar. We trekked along the river for 3 days. The campsites were: Singati Bazar, Suri Dobhan and Gonggar. At first, our route was along a dirt road that was built for the purpose of developing a hydroelectric plant in a tunnel drilled into a solid rock. The area is poor but not too remote as it is relatively close to Kathmandu with a daily bus connection. The lowland towns of Nepal seem very far removed from the clean world of ice and snow that is visible on the horizon. Unfortunately, many of the inhabitants of those towns have never ventured into the high Himalaya.

October 25, 2010 Simian 2,100m

On the fifth day of our trek in the sunny weather, we passed series of spectacular waterfalls dropping steeply from the high hills above straight into the Tama Koshi River. We crossed a hanging bridge and climbed steeply out of the Tama Koshi River valley with north to south orientation in order to join the Rowalling Valley with East to West orientation.

The climb out the narrow valley was up a steep staircase that in places seemed to ascend almost vertically. The stairs were wet from the mist and overgrown with lush vegetation. We arrived in a small village of Simigaon at the mouth of the Rowaling Valley. From that spot we could see a 7,143m high mountain called Menlungtse in Tibet behind the ridge of lower peaks. The main backdrop however was GauriSnkar, a massive 7,183m high peak dominating the head of the Tama Koshi Valley. Although located close to Kathmandu and the road, it is not climbed often. It is imposing and steep with granite walls too vertical to permanently hold ice or snow.

The people of Simagaon were very friendly. Our crew had a night party with porters from another group that was also going up to the Teshi Labtsa Pass. We purchased a small goat for the porters who killed it and cooked the meat for all of us. Since I saw the goat before it was killed, I could not eat it after. The porters were totally drunk on chang (the local beer) and the party got rowdy after dark with much dancing and loud singing. At sunset, we had a great view of GauriSankar from the village when the entire mountain was glowing bright yellow and then orange.

October 26, 2010 Dong

On October 26th we trekked to Dong with a nice relaxing camping spot by a river. It was an uneventful walk in the forest. The weather was nice and sunny, a perfect day for hiking. We enjoyed the relaxing pace and the sound of flowing river. The river we were now following originates at Tso Rolpa Lake formed high up the valley by a collapsed moraine. We would pass that lake in a few days and venture into the realm of ice beyond. The lake presents a grave danger to the entire valley in an event of an earthquake. It is constantly monitored and flood warning sirens can be seen in each village along the valley. Although it is hard to believe that any of them work and that the local people, in case of an earthquake, would have ample time to run for a higher ground.

October 27, 2010 Beding 3,700m

The following day we trekked to Bedding situated at and elevation of 3,600m. Beding is the last major village before the trail ascends steeply to the Tso Rolpa Lake and the Teshi Labtsa Pass. Bedding is situated at the bottom of the southeast flank of GauriSankar. The steep rock of the mountain loom above the village with white glaciers high up. At the entrance to the village, there is a small temple (gompa) at which David and I stopped to check it out. We were pulled into the gompa by a half drunk local guy who offered us boiled potatoes. The man claimed to have been an extra in the Sven Years in Tibet movie and have met Brad Pitt. He was missing all of his fingers and apparently lost them on a climb of Manaslu. He also claimed to have climbed on Dhaulagiri with Chris Bonnington. Inside the gompa, a group of old ladies were cooking up a storm. David and I provided them with a welcome diversion and much laughter. It seemed that we did not need to say or do anything to make them explode into fits of laughter just by looking at us. After our visit to the gompa we walked around the town where we encountered more drunk locals, one old lady particularly drunk passed out in the middle of the road. The village was quite poor and dirty with houses shared between people and animals. The usual setup is for the people to sleep upstairs and for the animals to occupy the lower floor. The flies from the animal quarters migrate to the upper salons and make the living conditions rather biblical.

October 28 and 29 2010 Nagaon 4,180m

From Beding, we ascended to Na at 4,180m where we spent two nights. Na (or Nagaon) is situated directly at the base of Kang Nachugo, a prominent peak of 6,737m that is situated on the border between Nepal and Tibet. Na serves as a summer pasture for the villagers from Beding and as such is not a permanently inhabited on year round basis. In the winter it must receive significant snowfall blocking all access from the valley below. Mount Chekigo 6,257m and Mount Kang Nachugo 6,737m form a steep rock wall hugging the entire village. Looking at these peaks it is deceiving to assume that they are easy to climb and accessible. The scale of the terrain is so massive and everything around is so big. Without any point of reference, things look closer and smaller than they really are. I experienced the same illusion during my travels in the high Arctic. A valley that looked small and near, required an entire week to traverse. Mt. Menlungtse in Tibet, is just behind Na and is accessible by an ancient pass between Mt. Chekigo and Mt. Kang Nachugo. I would like to visit this area one day if possible.

On the way to Na, we passed an isolated Buddhist hermitage with a spectacular view of the entire Rowaling upper valley and the snowy peaks above it. It would be a fantastic place to spend a week or two contemplating the nature of OM. We passed by large boulders with paintings of Tibetan deities and guardians. The prayer flags were also more common indicating that we were now entering the realm of Buddhism.

The following day, we did an acclimatization walk to above 5,000m beside the Yalung Glacier in preparation for the time required at higher altitudes in the days ahead. The walk was very tiring as we ascended 1,100m to above 5,000m in short time. When I get to 5,000m for the first time, I find the effort quite exhausting. The tiredness creeps up quite suddenly and all of a sudden I am out of energy. Every step higher is quite an effort and all I want to do it just sit and rest. I do suffer from serious FOMO in situations such as this and the desire for a better view propels me higher despite better judgement. Pushing harder, I hit the wall for the first time on the trip. The views from the 5,000m spot were fantastic though and worth the effort. We had clear blue sky and no wind. On the left side was Mt. Chukiyma Go 6,258m, in the distance the backside of GauriSankar 7,135m. Kang Nachugo blocked the view of the Menlungtse in Tibet. We could see however, directly into a valley that is crowned by Dranag Ri, a 6,800m peak. The glacier that flows from Dragnag Ri is called Rowaling Glacier like the glacier that we are going to follow to the Teshi Labtsa pass. The valley we were looking at had many high peaks that lined the east side of the glacier. On the east side, Tsoboye, a large 6,000m peak that was climbed by Tomas Humar dominates the confluence of the two Rowaling glaciers. Had we climbed a little higher to a Yalung La pass located at 5,310m, we could had seen the summit of Cho Oyu peaking on the horizon. Frankly, I did not have enough energy to go that last 200m.

After we got back to the tent in Na, I was very tired and all I could think of was drinking water. In the evening we hiked up above the campsite to the bottom of Kang Nachugo to a spectacular waterfall. We watched the clouds swirling up the valley from below. The sunset was fantastic. It illuminated the entire wall of Kang Nachugo in a full spectrum of colors from yellow to maroon.

It was a fantastic spot to spend the acclimatization day in. We were full of anticipation for what was ahead of us.

October 30, 2010 Kabug 4,561m